dublab :: Pharoah Sanders

“Accept everything. Accept other people just the way you accept yourself.” – Pharoah Sanders

Pharoah Sanders philosophy and music exist beyond thought and feeling. They originate from a spiritual core within the earthly vessel of a healer and giver, but resonate and reverberate at a frequency available to anyone – or anything – with an antenna aimed at the depths of the universe.

Floating the same frequency is dublab, the Los Angeles-based, non-profit radio station that has provided a platform for adventurous sound since 1999. dublab’s principles directly align along the same astral plane that Pharoah Sanders has traveled over the course of his prolific recording career.

With a triple ripple of Sanders’ Tauhid, Jewels Of Thought and Summun Bukmun Umyun – Deaf Dumb Blind newly editioned on Anthology Recordings, the label asked three of dublab’s deepest heads — Mark “Frosty” McNeil, Carlos Niño, and Mark Maxwell — to examine these albums under an intimate lens.

Placed in each of the three pyramid corners of this latest appraisal of Sanders’ work you’ll discover a different perspective than the one before, though each is as personal as it is perennial. It is this path of the individual to the infinite that Pharoah explored and that we invite you to journey too.

Stream + Pre-Order

Tauhid / Jewels of Thought / Summun Bukmun Umyun (Deaf Dumb Blind) / Deluxe Bundle

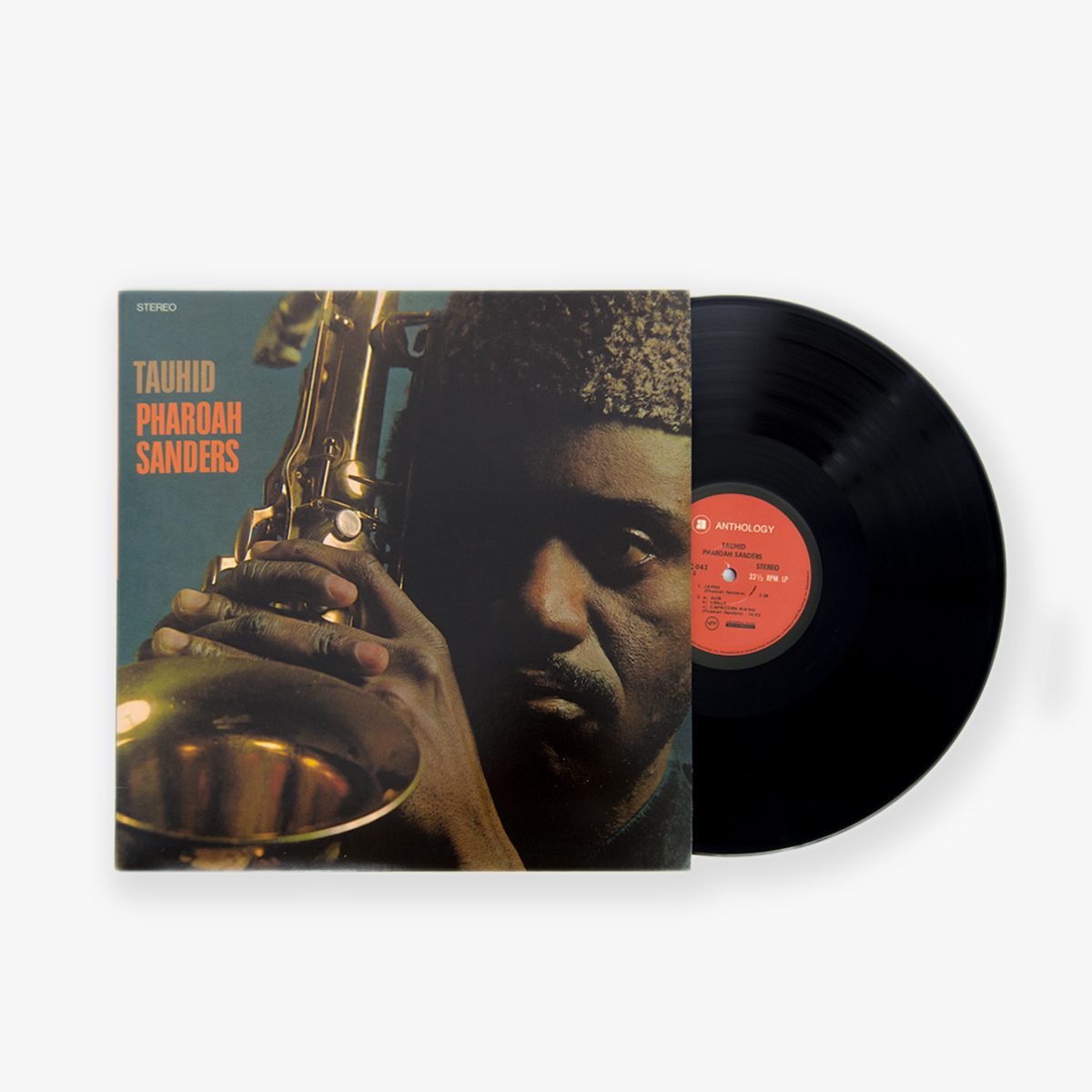

Tauhid

Pharoah’s First (ESP-Disk; 1965) was technically Pharoah Sanders’ debut release as a leader, but many – probably even Sanders himself – considered it to be something of a false start. The musicians on this date appeared to be playing from a post-bop paradigm that Sanders was determined to rise above. Nevertheless, two side long tunes were recorded in September of 1964 that have their moments but offer little evidence of the transcendence Pharoah was seeking. The LP was released the following year.

Fortunately, a new beginning was in the offing. A very auspicious beginning with far reaching repercussions.

In June of 1965, Pharoah entered Rudy Van Gelder’s legendary studio in Englewood Cliffs, NJ to assist John Coltrane with his free jazz classic, Ascension (Impulse; 1965). By September, Sanders was an official member of the legendary saxophonist’s iconoclastic ensemble. Coltrane was/is an artist of nearly unparalleled stature within the music and as such held considerable sway at his label. It’s no coincidence that the following year Coltrane’s younger bandmate completed the first of several important recordings for Impulse records.

“[In 1966] I wanted to record Pharoah Sanders for ABC. It took me two months to get approval to record him and no one wanted to spend any money”

-Bob Thiele, Producer

The Tauhid session took place back at Van Gelder’s studio on November 15, 1966. It was a Tuesday sandwiched between weekend dates with Coltrane at Temple University (Philadelphia) and The Village Vanguard (NYC).

The recording veteran among them was bassist Henry Grimes. He had contributed to records by jazz A-listeners such as Lee Konitz, Sonny Rollins and Archie Shepp since the late 50’s. Drummer Roger Blank had one major label (MGM) recording credit under his bealt and (like Pharoah) had played and recorded with Sun Ra. The date was a maiden voyage for the remaining musicians.

Dave Burrell would go on to become a major pianistic force in the music and remains active to this day. Sonny Sharrock’s strikingly edgy tone, bristling with intensity had not been heard in jazz before. A true original, he would make waves in and outside of jazz until his death in 1994. Nat Bettis eventually recorded four LP’s with Sanders as well as doing dates into the 90’s with Art Blakey, Donald Byrd, Gary Bartz Ntu Troop, and Norman Connors.

The LP opens in somber but stately fashion with “Upper And Lower Egypt”. Sharrock provides a novel yet perfectly apt drive to the rubato opening. There are bells and strange, beautiful percussion colors from Bettis. When the music subsides Grimes fills the breach with a short arco bass solo. He’s soon joined by the leader’s voice which makes its first appearance via piccolo. Pharoah continues punctuated by occasional tom and cymbal hits and Grimes’ bass (both bowed and plucked). This gives way to a brief drum and percussion duet before Grimes returns with a rhythmic figure that pulls the rest of the rhythm section back into the soulful vamp that becomes “Lower Egypt”. It’s at this point, a full third of the way into the LP, where Sanders’ muscular tenor sax finally enters with the song’s melody. Following a crescendo of multiphonic cries through the tenor, Sanders puts down the horn to sing/scat the melody to powerful effect.

Despite being the major label premiere of a “free jazz firebrand”, Sander’s delivers melodies that are beautifully lyrical, memorable and even catchy. Admittedly, the next one is not his own. “Japan” is a traditional folk melody (a “souvenir” he brought back from his recent trip to the country with Coltrane), but Pharoah delivers it to a new audience with a respectful and sincere reading.

“Aum” aka “Om” is one of Hinduism’s most important spiritual symbols; it’s a sacred sound. It’s also the title of the first part of the three song suite that closes Tauhid. For many, that title might conjure images of quiet meditiation. However, anyone missing the caustic pyrotechnics of Pharoah’s work in the Coltrane band can surely find it here. After a brief hi-hat workout and bass intro, Sanders enters on alto saxophone with all the tumult, heat and intensity of worlds being forged in the universal furnace. Sanders’ incendiary alto sax eventually dissolves into a sea of undulating chords and rhythms. Sharrock emerges with an effective solo of energy and sound that has little or nothing to do with the notes. When Sanders returns with his tenor, the piece transforms. We’ve now reached “Venus” which begins with another powerful, full throated melody and then takes a turn for the turbulent only to return to (then abandon) the melody.

Venus concludes with a short pizzicato bass solo that leads into the lovely and lyrical closing section “Capricorn Rising”.

Tauhid followed quite a trajectory. It starts out where all of humanity started out, in Africa (“Upper and Lower Egypt”). It then headed east with “Japan” and “Aum” and ultimately ends up in the stars (“Venus” and “Capricorn Rising”).

“…the record came out, everyone said, ‘What kind of crap is this? This isn’t going to sell.”

— Bob Thiele

When Thiele refers to “everyone” he meant the label brass. Tauhid saw an impressive release in 1967. It was noted in Billboard magazine’s “Four Star” jazz section (Dec. 9, 1967), came in #2 in Jazz & Pop’s (Volume 8, Issue 2) Top Twenty Jazz LP’s of 1968 and even won a “Modern Jazz Oscar” in Paris in April of 1969.

“Hey did we sign that Pharoah Sanders? On, sign him up now. Let’s get him.”

-Larry Newton, President ABC/Impulse 1967

Mark Maxwell

RISE / KPFK 90.7fm Los Angeles (1998 – present)

Jewels Of Thought

– facets explored Mark “Frosty” McNeill

Peace is a united effort for co-ordinated control

Peace is the will of the people and the will of the land

With peace we can move ahead together

We want you to join us this evening in this universal prayer

This universal prayer for peace for every man

All you got to do is clap your hands

One two three

One two three

One two three

One two three

The invocation opening Pharoah Sanders’ Jewels of Thought is a call to action, an appeal for peaceful reaction. ‘Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah,’ is rooted in Sufism and imbued with prescient potency. Delivered in Leon Thomas’ elated ululation, it is pure, optimistic sound power. This kinetic fluidity spans the expressive album.

Hum-Allah, hey

Hum-Allah, hey

Hum-Allah, hey

Hum-Allah

When Pharoah Sanders let loose Jewels of Thought in 1969, he was rising to meet the need of the time. A summoning birthed in a climate of war and inequality. These manmade afflictions are still with us, but so thankfully is Sanders’ flare, arcing into infinity with undimmed vigor.

Prince of peace won’t you hear our pleas

And ring your bells of peace

Let loving never cease

Prince of peace won’t you hear our pleas

And ring your bells of peace

Let loving never cease

Jewels of Thought overflows with high vibrations activated by Sanders’ assembly of master musicians: Lonnie Liston Smith, Roy Haynes, Cecil McBee, Idris Muhammad, Richard Davis, and Leon Thomas. Pharoah’s court comes well equipped for their rhapsodic task. They spill chimes, kalimba, percussion, piano, African flute, voice, bass and drums into the cosmos. These sonic constellations are spun into a fervor by Pharoah’s tenor saxophone, contrabass clarinet and reed flute.

With its primordial shimmer, the album’s second side, ‘Sun in Aquarius’ is an active meditation charged with life force. It is a tome balancing serenity with shrieks in a course carved towards transcendence. While peace is the destination, Sanders seeks this space by alternately spitting flames at fire and caressing the atmosphere. His ferocious blasts shred illusions to reveal the blissful core of being.

This is music that breaks the bonds of expectation, seeking freedom in form and intention. The aural prayers on Jewels of Thought, are expansive vistas viewed through the scope of a universal mindstate. This is not analytical music—it is feeling, breathing and loving music. Jewels of Thought is a vessel into which Sanders poured his soul so that we may revel in ecstatic unity.

Hum-Allah, hey

Hum-Allah, yeah

Hum-Allah, hey

Hum-Allah

Summun Bukmun Umyun (Deaf Dumb Blind)

It’s said that spirit exists beyond space or time. This may explain why there’s a freshness about the music on Summun Bukmun Umyun – Deaf Dumb Blind that belies its 47 years. This recording was, indeed, a spiritual undertaking.

Sanders’ 1966 debut recording for the Impulse label bears the Arabic title Tauhid. This translates to “the oneness of god”, a core concept of Islam. His follow up, Karma, yielded the chart topping composition “The Creator Has A Master Plan”. Jewels Of Thought (Pharoah’s third Impulse LP) featured the standout track “Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah-Hum-Allah”. So Summun Bukmun Umyun falls comfortably into this pattern of spiritual subject matter.

The actual phrase summun bukmun umyun comes from the Koran. It refers to non-believers. That being said, Pharoah’s title choice may have more of a political significance than a spiritual one. The phrase was in popular usage at the time among the followers of Elijah Muhhamad and most likely indicates an affinity for the Nation Of Islam’s black power message.

Pharoah Sanders’ afrocentricity would soon go on to be more unequivocally articulated with recordings such as Live At The East and Black Unity, but on this 4th Impulse recording it seems to exist more as artistic aesthetic than political manifesto.

The album’s title track is rich with the African primacy of rhythm. With the exception of bassist Cecil McBee, the entire octet is involved in contributing a muscular percussion. This polyrhythmic aspect also contains strong melodic and harmonic elements in the form of Nat Bettis’ balafon and Lonnie Liston Smith’s stacatto two chord piano vamp. The resultant groove provides an earthy accessibility that grounds the side long composition even as it propels it. It should be noted that though McBee is not playing a percussion instrument, per se, it’s his deep syncopated bass line that establishes the powerful groove. Two minutes and twenty seconds into this groove we’re treated to the recording debut of Sander’s throaty, ecstatic cry on soprano saxophone. It is a voice full of joyous intensity and vitality. A minute later Gary Bartz’s familiar alto sax enters in the right channel with Woody Shaw’s distinctive trumpet following soon after on the left channel. From this point there is an organic unfolding of saxophone, piano, balafon, drum, flute and whistle solos as well as exuberant melodic vamping that ultimately trail off after the 21 minute mark like a desert caravan breaking camp at dawn.

Producer Ed Michel’s hands-off approach to production proves to be a good fit for an artist of Pharoah’s vision. It allows each of the tunes to progress at their own pace. It also leaves room for non-traditional instrumentation and techniques.

What emerges is natural music in service of a high vibration and this continues – albeit with a different vibration – on the record’s flip side.

Interestingly, that flip side is Smith’s adaptation of a traditional gospel piece.

“I look at all religions and just put them all into one, you know. That’s what I do. It’s like a personal kind of thing. I don’t go to a church or mosque, I’m here every day doing my own thing. But I try and pray all the time. The day’s like one big prayer to me, not at any one time.”

“Let Us Go Into The House Of The Lord” is at times reminiscent of John Coltrane’s “Welcome” from the 1966 Impulse recording Kulu Se Mama. Pharoah appears on that album as well, but not on that particular tune.

From the beginning, the ensemble evokes an atmosphere of deep reverence and devotion. Of course, much of that prayerfulness comes directly from the bell of Pharoah’s horn. He receives adept support from Smith’s majestic piano arpeggios, a plenitude of bells and shakers, and ex-Sun Ra drummer Clifford Jarvis’ ever tasteful tom and cymbal work, but McBee’s masterful arco bass work performs as much heavy lifting as anyone involved. The bassist’s bowed contributions keep the music gently climbing throughout it’s unhurried 17 minute and 46 seconds.

Floating and tranquil the piece meanders languidly yet manages to reach a stunning climax roughly at half way point.

It is not a climax in the common sense. It is hushed and incredibly peaceful. The saxophone quiets, the bells and arpeggios recede. Smith reaches into the piano to strum the strings like a harp. It’s here that the bass emerges from his supporting role with a tender vocal quality that is astonishing to behold. It’s so intimate that you almost feel embarrassed; almost as though you’ve inadvertently eavesdropped on the most private of conversations.

And you have; a conversation with the most high. However, there’s no need for embarrassment.

Mexican Summer

Mexican Summer